The Ultimate Guide to Capacitors: Everything You Need to Know

More from the Category

Capacitors are indispensable components in electronic circuits, designed to store and release electrical energy as needed. They serve a critical role across a broad spectrum of applications, from consumer electronics to power systems, thanks to their ability to manage energy flow, filter signals, and stabilize voltage. Their straightforward construction and availability in numerous shapes and sizes make them both practical and versatile for diverse use cases.

In modern electronic devices, capacitors are crucial for maintaining system stability and optimizing efficiency. They contribute to smooth power delivery, noise reduction, and improved circuit performance. A deeper understanding of their operation—centered around the electrostatic field generated between their conductive plates—enables engineers to design circuits with precision and reliability. Additionally, advancements in capacitor materials, such as ceramic and polymer dielectrics, have enhanced their durability, energy density, and performance in high-frequency and high-temperature environments.

How Capacitors Work

A capacitor is a fundamental electronic component composed of two conductive plates separated by a non-conductive material called the dielectric. When voltage is applied, electric charges accumulate on the plates: one plate gains a positive charge, while the other acquires a negative charge. This separation of charges creates an electrostatic field between the plates, which is the mechanism by which the capacitor stores energy.

The capacity of a capacitor to store electrical energy is quantified as its capacitance, measured in farads (F). Capacitance depends on three key factors: the surface area of the plates (larger areas store more charge), the distance between the plates (closer plates increase capacitance), and the dielectric material’s properties (materials with higher permittivity enhance capacitance). One farad represents the ability to store one coulomb of charge at a potential difference of one volt.

The relationship between the charge stored and the voltage applied is proportional. When a voltage source is connected, current flows as the capacitor charges. Initially, the current is at its peak, but as the capacitor approaches its full charge, the current decreases until it ceases altogether. At this point, the voltage across the capacitor equals the applied voltage, and the capacitor maintains its charge.

Capacitors also exhibit dynamic behavior when the voltage changes. If the voltage across the plates increases or decreases, the capacitor either charges or discharges to match the new voltage. The time required for this adjustment is determined by the RC time constant, a product of the capacitor’s capacitance and the resistance of the circuit. This characteristic is critical for applications like voltage regulation, signal filtering, and power smoothing.

Modern capacitors are indispensable in electronic devices, ensuring stability and efficiency in circuits. They are widely used for energy storage, voltage smoothing, and coupling signals between different stages of electronic systems. Recent advancements in capacitor technology have introduced materials with higher energy densities, extended temperature ranges, and improved reliability, making them even more versatile for cutting-edge applications like renewable energy systems and electric vehicles.

By understanding the operating principles of capacitors, including the role of the electrostatic field and factors affecting capacitance, engineers can better design systems that optimize performance and reliability.

How Do Capacitors Work in Series Configurations?

Capacitors connected in series are commonly used to achieve higher voltage ratings than a single capacitor can handle alone. In a series configuration, the overall capacitance decreases, but the combined voltage rating increases. This makes series setups ideal for applications requiring high voltage capacity while maintaining compact designs.

Advantages of Using Series Configurations

- • Increased Voltage Rating: A key benefit of series configurations is the ability to handle higher voltages. The total voltage rating of the setup is the sum of the individual capacitors' voltage ratings, enabling operation in high-voltage environments.

- • Balanced Charge Distribution: In a series configuration, the same charge (Q) is distributed across all capacitors, ensuring balanced operation regardless of individual capacitance differences.

- • Enhanced System Reliability: Using multiple capacitors in series can improve overall system reliability. If one capacitor fails (open circuit), the others can continue operating, albeit with a reduction in total capacitance.

Calculating Capacitance in Series

To determine the total capacitance (C_total) of capacitors in series, use the formula:

[ \frac{1}{C_{total}} = \frac{1}{C_1} + \frac{1}{C_2} + \frac{1}{C_3} + \ldots ]

This equation shows that the total capacitance is always less than the smallest individual capacitor in the series. For example, if you have two capacitors, each rated at 10µF, the total capacitance would be:

[ \frac{1}{C_{total}} = \frac{1}{10µF} + \frac{1}{10µF} = \frac{1}{5µF} ]

Thus, ( C_{total} = 5µF ).

Practical Applications

- • High-Voltage Power Supplies: Series capacitors are frequently used in high-voltage power supplies, ensuring the circuit can handle elevated voltage levels safely and efficiently.

- • Audio Equipment: In audio crossover networks, series capacitors help block low-frequency signals, protecting delicate high-frequency drivers from damage.

- • Signal Filtering: Series capacitors play a crucial role in signal processing, isolating specific frequency ranges in electronic circuits.

- • Pulse Circuits: Series configurations are often used in pulse circuits, where rapid charging and discharging are required for timing or control applications.

Key Considerations for Series Configurations

- • Voltage Balancing: To maintain even voltage distribution, capacitors in series should have identical values and characteristics. Using high-quality capacitors from trusted suppliers like Microchip USA helps ensure consistency.

- • Leakage Current: Leakage currents can differ between capacitors, causing imbalanced voltages in the series. Careful selection and testing of capacitors are essential to mitigate this issue.

- • Safety Margins: Always ensure that the voltage rating of the capacitors collectively exceeds the operating voltage of the circuit, allowing for safety margins against voltage surges.

- Capacitors in series configurations offer significant advantages in high-voltage applications. With proper selection, design, and attention to balancing considerations, they enhance performance, reliability, and efficiency across various electronic systems. Recent advancements in capacitor materials and manufacturing have further improved their capability to handle high-stress environments, making them indispensable in modern electronics.

Understanding Impedance and Reactance in Capacitors

When working with capacitors, two essential concepts frequently arise: impedance and reactance. These properties govern how capacitors interact with alternating current (AC) circuits, influencing their performance in various applications.

Reactance

Reactance refers to the opposition a capacitor presents to AC flow. For capacitors, this is specifically called capacitive reactance (Xc) and is measured in ohms (Ω). Capacitive reactance is frequency-dependent and decreases as the AC frequency increases. This relationship is mathematically expressed as: Xc=12πfCX_c = \frac{1}{2 \pi f C}Xc =2πfC1

Where:

- • XcX_cXc : Capacitive reactance (Ω)

- • fff: Frequency of AC (Hz)

- • CCC: Capacitance (F)

This formula highlights that capacitors allow higher-frequency signals to pass more easily, making them integral to applications like signal filtering and AC coupling.

Impedance

Impedance (ZZZ) is a comprehensive measure that combines resistance (RRR) and reactance (XXX) into a single value, encompassing all forms of opposition to current flow in a circuit.

- • In a purely capacitive circuit, impedance equals capacitive reactance: Z=XcZ = X_cZ=Xc

- • In circuits with both resistance and reactance, impedance is calculated using the phasor sum: Z=R2+Xc2Z = \sqrt{R^2 + X_c^2}Z=R2+Xc2

- Impedance is critical for analyzing AC circuits as it dictates how effectively a capacitor operates under specific conditions.

Key Takeaways

- • Capacitive Reactance: Governs how easily AC flows through a capacitor, inversely related to the AC frequency.

- • Impedance: A broader measure that accounts for all opposition to current, essential for designing and troubleshooting AC circuits.

- Understanding these concepts enables precise predictions of a capacitor’s behavior in complex AC systems, ensuring effective design and efficient operation.

Breakdown Voltage in Capacitors

The breakdown voltage of a capacitor is the maximum electric field strength that its dielectric material can withstand before failing. Exceeding this limit causes the dielectric to become conductive, leading to catastrophic failure in the form of a short circuit.

Critical Factors of Breakdown Voltage

- • Electric Field Intensity: The electric field strength within the capacitor increases with voltage. Once this field exceeds the dielectric's threshold, breakdown occurs.

- • Dielectric Material: The insulating material between the capacitor’s plates determines the breakdown voltage. High-quality dielectrics like ceramic, polymer, or tantalum can significantly improve a capacitor's voltage-handling capabilities.

- • Failure Point: The breakdown voltage is the threshold at which the dielectric fails, allowing current to pass through. This marks the operational limit of the capacitor.

Key Points to Consider

- • Operational Safety: Always select capacitors with a breakdown voltage comfortably higher than the maximum expected operating voltage to ensure reliability.

- • Material Selection: Advanced dielectric materials can enhance breakdown voltage and improve capacitor performance in demanding environments.

- • Applications: High-breakdown-voltage capacitors are essential in high-power circuits, surge protectors, and power transmission systems.

- By understanding and respecting the breakdown voltage, engineers can design systems that maximize capacitor longevity and prevent premature failures. Combined with impedance and reactance knowledge, these principles form the foundation for using capacitors effectively in modern electronics.

Understanding the Q Factor of a Capacitor

- The Q factor, or Quality factor, is a vital parameter for evaluating a capacitor’s efficiency in AC circuits. It represents the ratio of a capacitor’s reactance to its equivalent series resistance (ESR), providing insight into how effectively the capacitor performs with minimal energy loss.

Key Concepts

· Capacitance: The ability of a capacitor to store and release electrical charge.

· Dielectric Materials: Insulating materials between the capacitor plates that influence capacitance and Q factor.

· Reactance and Impedance: The capacitor’s resistance to changes in current flow, critical for understanding AC behavior.

· Parasitic Inductance: Unintended inductance in a capacitor, which can lower the Q factor at higher frequencies.

Calculating the Q Factor

The Q factor of a capacitor can be determined using the following steps:

Determine Reactance (XcX_cXc ):

Xc=12πfCX_c = \frac{1}{2\pi f C}Xc =2πfC1

Where:

· XcX_cXc : Capacitive reactance (Ω)

· fff: Frequency of the AC signal (Hz)

· CCC: Capacitance (F)

Identify Equivalent Series Resistance (ESR): The ESR is typically provided in the capacitor’s datasheet and represents the real-world losses in the capacitor.

Compute Q Factor:

Q=XcESRQ = \frac{X_c}{ESR}Q=ESRXc

The higher the Q factor, the more efficient the capacitor, with less energy dissipated as heat.

Importance of the Q Factor

- • Signal Integrity: A high Q factor ensures better signal fidelity, making it essential in filtering and tuning circuits.

- • Energy Efficiency: Capacitors with higher Q factors experience minimal energy loss, which is particularly important in resonant circuits and high-frequency applications.

- • Performance Indicator: The Q factor serves as a benchmark for a capacitor’s overall performance under AC conditions, especially in demanding environments.

Practical Considerations

- • Frequency Dependence: The Q factor varies with frequency, so it must be evaluated at the operating frequency of your application.

- • Material Selection: Low-loss dielectric materials, such as polypropylene or ceramic, contribute to higher Q factors.

- • Parasitic Elements: Minimizing parasitic inductance and resistance is critical, especially in high-frequency circuits, to maintain a high Q factor.

- • Thermal Stability: ESR and Q factor can fluctuate with temperature. Select capacitors with stable characteristics across your circuit’s operating temperature range.

- The Q factor is a cornerstone of capacitor performance in AC circuits, directly impacting efficiency, signal clarity, and energy conservation. By understanding and optimizing this parameter—through careful component selection and circuit design—you can ensure enhanced performance, reduced losses, and longer-lasting electronic systems in both everyday and advanced applications.

Understanding Parasitic Inductance and Resistance in Capacitors

- In an ideal scenario, capacitors would function purely based on their capacitance. However, real-world capacitors exhibit imperfections, such as parasitic inductance and resistance, which can impact their performance, particularly in high-frequency applications.

What is Parasitic Inductance?

Parasitic inductance refers to the unintended inductive effects within a capacitor caused by its physical construction. Key contributors to parasitic inductance include:

- • Conductors and Lead Wires: The wires and connections used to connect the capacitor to a circuit generate small magnetic fields as current flows through them.

- • Internal Connections: The design and materials inside the capacitor also contribute to inductance.

- These inductive effects become increasingly significant at high frequencies, where they can interfere with the capacitor’s intended function by shifting its impedance and altering its behavior in the circuit.

What is Parasitic Resistance?

Parasitic resistance is the unintended resistive property of a capacitor, caused by:

- • Conductive Materials: The leads, plates, and internal connections introduce resistance.

- • Dielectric Material: Some dielectric materials have inherent resistive properties that add to the overall parasitic resistance.

- This resistance causes energy losses as heat, which can reduce the capacitor’s efficiency and accuracy. In applications like high-frequency circuits or precision signal processing, even small resistances can lead to noticeable performance degradation.

Key Points to Remember

- • Construction Elements: Lead wires, internal connections, and the choice of dielectric material are primary contributors to parasitic inductance and resistance.

- • High-Frequency Impact: Parasitic inductance and resistance become more pronounced at higher frequencies, potentially degrading the capacitor’s performance. They can cause signal distortion, energy loss, or unwanted resonances in circuits.

- • Energy Dissipation: Parasitic resistance leads to heat generation, which can reduce the efficiency of a capacitor and, in extreme cases, affect the reliability and lifespan of the circuit.

Minimizing Parasitic Effects

- • Low-Inductance Design: Use capacitors with short leads, tight internal connections, or surface-mount technology (SMT) to minimize parasitic inductance.

- • High-Quality Dielectrics: Select capacitors with low-loss dielectric materials to reduce resistive losses.

- • Frequency-Optimized Components: For high-frequency applications, choose capacitors specifically designed to operate efficiently at your circuit’s frequency range.

- • Circuit Design: Include compensatory components, such as series resistors or ferrite beads, to mitigate the effects of parasitics.

- Understanding and addressing parasitic inductance and resistance are essential for designing high-efficiency and reliable electronic systems. These factors, though small in magnitude, can significantly influence capacitor behavior, particularly in high-speed, precision, or high-frequency circuits. By carefully selecting components and optimizing circuit designs, engineers can minimize parasitic effects and enhance overall system performance.

Material Choice and Configuration in Capacitors

While all capacitors operate on the same basic principle of storing energy through an electric field, the choice of materials and configuration can vary significantly. These differences are critical in determining a capacitor’s performance characteristics and suitability for specific applications. The dielectric material and the plate configuration directly impact key factors such as capacitance, voltage rating, and tolerance.

Dielectric Material

The dielectric material—the insulating layer between the capacitor plates—is one of the most important determinants of a capacitor’s properties. Common dielectric materials and their characteristics include:

Ceramic:

· High dielectric constant, enabling compact designs with high capacitance values.

· Ideal for general-purpose, high-frequency, and temperature-stable applications.

- Electrolytic:

· High capacitance per unit volume, suitable for energy storage and filtering.

· Polarized, meaning they must be used in circuits with a fixed polarity.

- Film:

· Low ESR and excellent stability over time.

· Commonly used in high-precision and power applications.

- Tantalum:

· High reliability and good performance in compact packages.

· Often used in portable devices and sensitive circuits.

- Polymer:

· High capacitance and low ESR, providing excellent performance in high-frequency applications.

· Suitable for energy storage and decoupling in modern electronics.

Plate Configuration

The configuration of the plates also plays a significant role in determining the capacitor’s behavior:

Parallel Plate:

· Standard design for most capacitors, offering a predictable capacitance value based on plate area and separation.

Multilayer:

· Found in multilayer ceramic capacitors (MLCCs), these provide higher capacitance in a compact size by stacking multiple plate-dielectric layers.

Wound Foil:

· Used in electrolytic and film capacitors, where plates are wound into a cylindrical shape to save space.

Interdigitated:

· Common in specialized applications, this configuration increases surface area to achieve higher capacitance values in compact spaces.

Performance Factors Influenced by Material and Configuration

• Capacitance: Determined by the dielectric constant of the material and the effective surface area of the plates.

• Voltage Rating: The breakdown voltage depends heavily on the dielectric material’s properties and the distance between the plates.

• Tolerance: High-precision applications require materials and configurations that minimize variations in capacitance.

• Temperature and Frequency Stability: The dielectric material and plate design dictate how well a capacitor performs across varying temperatures and frequencies.

Applications

• High-Frequency Circuits: Ceramic and polymer capacitors excel due to their low ESR and excellent stability.

• Energy Storage: Electrolytic and tantalum capacitors are ideal for providing high capacitance in compact sizes.

• Signal Filtering: Film and ceramic capacitors are commonly used for their precision and stability.

By carefully selecting the dielectric material and optimizing the plate configuration, designers can tailor capacitors to meet the specific demands of modern electronic systems. These decisions not only affect performance but also play a crucial role in ensuring reliability and efficiency in applications ranging from consumer electronics to industrial systems.

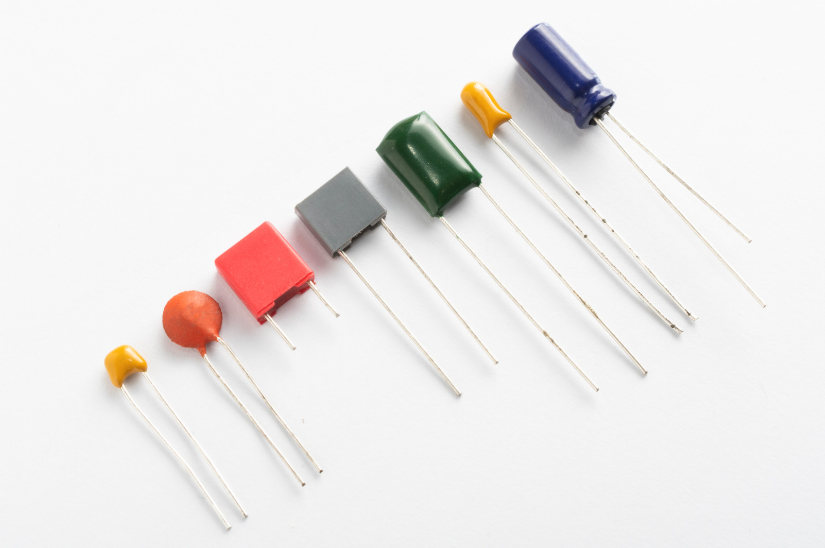

Types of Capacitors

Capacitors come in a variety of types, each with unique properties suited for specific applications. Understanding these differences is crucial for selecting the right capacitor to meet performance requirements in electronic circuits. Below are the most common types of capacitors and their characteristics.

Ceramic Capacitors

Ceramic capacitors are the most commonly used capacitors due to their affordability, versatility, and availability in various shapes and sizes.

- • Dielectric Material: A ceramic material serves as the dielectric, offering a high dielectric constant.

- • Non-Polarized: They can be connected in either direction, making them suitable for a wide range of applications.

- • Applications: Ideal for high-frequency applications such as filtering, tuning, and decoupling.

- Advantages:

- • High capacitance per unit volume.

- • Low cost and availability in small sizes.

- Considerations: Ceramic capacitors have lower tolerance and are classified into different classes (Class 1 for high stability and Class 2 for higher capacitance with reduced stability).

Electrolytic Capacitors

Electrolytic capacitors are polarized, meaning they have specific positive and negative terminals. These capacitors are used in applications requiring high capacitance values, such as power supplies and audio amplifiers.

- • Dielectric Material: An electrolyte, which can be either liquid or solid.

- • Applications: Suitable for low-frequency applications, such as smoothing voltage fluctuations.

- Advantages:

• High capacitance in a compact form.

- Limitations:

- • Sensitive to temperature and frequency, making them less effective in high-frequency circuits.

- • Higher tolerance than ceramic capacitors, but prone to leakage current and parasitic inductance.

Film Capacitors

Film capacitors use a thin film of metal or metalized plastic as the dielectric, offering excellent performance in applications requiring precision and low distortion.

- • Dielectric Material: Thin metalized film or plastic film.

- • Non-Polarized: Suitable for AC and DC circuits.

- • Applications: Commonly used in high-performance audio and video equipment, and signal filtering.

- Advantages:

- • High accuracy and stability over time.

- • Low distortion and low equivalent series resistance (ESR).

- Limitations:

- • Lower capacitance per unit volume compared to ceramic and electrolytic capacitors.

Tantalum Capacitors

Tantalum capacitors are similar to electrolytic capacitors but offer higher capacitance per unit volume, making them ideal for compact electronic devices.

- • Dielectric Material: Tantalum oxide.

- • Polarized: They must be used with correct polarity to avoid damage.

- • Applications: Found in portable electronics such as smartphones and wearables.

- Advantages:

- • High reliability and capacitance in small packages.

- Limitations:

- • Sensitive to overvoltage, which can result in failure.

Supercapacitors

Supercapacitors, also known as ultracapacitors or double-layer capacitors, are designed for high power density and energy storage.

- • Dielectric Material: Activated carbon provides a high surface area for charge storage.

- • Applications: Used in electric vehicles, renewable energy systems, and backup power supplies.

- Advantages:

- • High energy storage capacity compared to conventional capacitors.

- • Long lifespan and fast charging/discharging capabilities.

- Limitations:

- • Lower voltage ratings and capacitance per unit volume.

Filter Capacitor

A filter capacitor is a critical component in electronic circuits, designed to reduce unwanted noise and smooth out voltage fluctuations. By stabilizing power and minimizing interference, it enhances the performance and longevity of electronic devices.

- Key Functions of Filter Capacitors

- • Noise Reduction: Filter capacitors effectively suppress high-frequency noise, preventing unwanted signals from disrupting circuit operation. This is crucial in applications where signal integrity is essential, such as communication systems and precision electronics.

- • Voltage Smoothing: They help maintain a stable voltage level by filtering out ripples and fluctuations in power supplies. This ensures that connected components receive a consistent DC voltage, preventing malfunctions and extending the lifespan of sensitive electronics.

- How Filter Capacitors Work in Different Applications

- • In Power Supplies: When AC voltage is rectified into DC, it still contains residual fluctuations (ripples). Filter capacitors store and release charge as needed, converting pulsating DC into a smoother, more stable output. Without them, power supply inefficiencies could cause overheating and erratic performance in electronic devices.

- • In Audio Circuits: They eliminate hums and background noise, improving audio clarity in amplifiers, speakers, and recording equipment.

- • In Communication Systems: By filtering out interference, they help ensure clearer and more reliable transmission of signals in radios, telecommunication devices, and data processing equipment.

- Types of Filter Capacitors and Their Uses

- Electrolytic Capacitors

· Offer high capacitance values.

· Commonly used in power supply filtering due to their ability to handle higher voltages and currents.

· Ideal for applications requiring energy storage and bulk decoupling.

- Ceramic Capacitors

· Feature lower capacitance values but excellent high-frequency performance.

· Used in signal processing circuits to filter high-frequency noise.

· Preferred for their low equivalent series resistance (ESR), which makes them efficient in high-speed applications.

- Film Capacitors

· Provide stable and reliable performance over time.

· Used in precision filtering applications where minimal capacitance drift is required.

· Common in high-fidelity audio systems and power electronics.

- Real-World Applications of Filter Capacitors

- • Power Supply Units (PSUs): Ensure a steady voltage supply for computers, industrial machines, and consumer electronics, preventing erratic behavior due to voltage fluctuations.

- • Audio Equipment: Improve sound quality by eliminating background noise, ensuring clear and crisp audio output.

- • Communication Devices: Enhance signal clarity in radios, wireless networks, and telecom equipment by filtering unwanted interference.

- • Automotive Electronics: Used in electric vehicle power systems and onboard electronics to maintain stable voltage and reduce electromagnetic interference (EMI).

- Filter capacitors are indispensable in modern electronics, playing a vital role in noise suppression, voltage regulation, and circuit protection. Whether in power supplies, audio systems, or communication devices, their ability to filter and stabilize voltage ensures efficient, reliable operation across a wide range of applications.

Polymer Capacitors

- Polymer capacitors are a specialized class of capacitors that use a solid conductive polymer as the electrolyte instead of a liquid or gel. This innovative design enhances reliability, performance, and efficiency, making them a preferred choice in many modern electronic applications.

- Key Features of Polymer Capacitors

- • Enhanced Performance: Polymer capacitors exhibit low equivalent series resistance (ESR), significantly reducing power losses and improving filtering efficiency in power supply circuits. This makes them ideal for high-speed and high-efficiency applications.

- • Exceptional Stability and Longevity: Unlike traditional electrolytic capacitors, polymer capacitors are highly resistant to drying out and can withstand harsh environmental conditions, ensuring a longer operational lifespan with minimal degradation over time.

- • High Capacitance and Voltage Ratings: They offer higher capacitance values and wide voltage ratings, making them suitable for a range of applications, from compact consumer electronics to robust industrial and automotive systems.

- Structural Composition and Functionality

Polymer capacitors are composed of conductive layers separated by a dielectric material, allowing them to store and discharge electrical energy efficiently.

- Electrostatic Field Storage: Energy is stored in an electrostatic field, created by the potential difference between the conductive layers. When voltage is applied, one layer accumulates a positive charge, while the other holds a negative charge.

- Capacitance Measurement: The capacitance (measured in farads) depends on two key factors:

- · Surface Area of the Conductive Layers: A larger surface area increases capacitance.

- · Separation Distance: A smaller gap between layers enhances capacitance, improving overall charge storage.

Advantages and Considerations

- • Low Parasitic Effects: Polymer capacitors have minimal parasitic inductance and resistance, making them ideal for high-frequency applications such as RF circuits, power delivery networks, and high-speed data systems.

- • High Breakdown Voltage: These capacitors can tolerate high voltages before dielectric failure, increasing their reliability in demanding applications such as power converters and automotive electronics.

- • Minimal Leakage Current: Although all capacitors exhibit some leakage, polymer capacitors have lower leakage currents than many other types, improving efficiency in low-power and battery-powered devices.

- Applications of Polymer Capacitors

- • Consumer Electronics: Used in smartphones, laptops, and gaming consoles to enhance power efficiency and stability.

- • Power Management Systems: Provide reliable power smoothing and filtering in voltage regulation circuits.

- • Automotive and Industrial Equipment: Withstand high temperatures and harsh environments, making them ideal for electric vehicles (EVs), industrial automation, and aerospace systems.

- • High-Speed Computing: Improve power integrity in servers, GPUs, and data centers, where stable and efficient power delivery is crucial.

- Polymer capacitors offer superior performance, longevity, and stability, making them a top choice for modern electronic circuits. Their low ESR, high capacitance, and minimal parasitic effects ensure efficient operation in applications ranging from compact consumer gadgets to advanced industrial and automotive systems. With their ability to handle high frequencies and voltages, they are a key component in the next generation of electronic design.

Trimmer Capacitors

A trimmer capacitor is a small, adjustable capacitor designed for fine-tuning circuits where precise capacitance adjustments are required. Unlike fixed capacitors, trimmer capacitors can be manually adjusted to achieve optimal circuit performance, making them essential in calibration-dependent applications such as RF tuning, oscillators, and sensor circuits.

- Key Characteristics of Trimmer Capacitors

- • Adjustable Capacitance: Allows for fine-tuning circuit parameters by varying the capacitance within a specified range.

- • Compact Size: Small form factor makes them ideal for space-constrained designs in consumer electronics, communication devices, and industrial instruments.

- • Capacitive Range: Typically offers values ranging from a few picofarads (pF) to a few nanofarads (nF), making them suitable for high-frequency applications.

- • Stable Construction: Made from materials such as ceramic, mica, or plastic, ensuring stable electrical properties and long-term durability.

- • Multiple Mounting Options: Available in surface-mount technology (SMT) for modern compact circuits and through-hole technology (THT) for traditional PCB designs.

- Applications of Trimmer Capacitors

- • RF Circuits: Essential for adjusting the resonant frequency in radio transceivers, antennas, and tuning circuits.

- • Oscillators: Used to fine-tune the frequency stability of oscillators in signal processing and clock generation circuits.

- • Tuning Circuits: Critical for adjusting audio and video equipment, ensuring optimal signal clarity.

- • Capacitive Sensors: Applied in precision sensor designs, such as touch-sensitive interfaces and environmental monitoring systems.

- • Medical Equipment: Utilized in diagnostic and monitoring devices where precise frequency calibration is crucial.

- Advantages of Trimmer Capacitors

- • High Precision: Provides fine control over circuit behavior, enhancing efficiency and accuracy.

- • Adjustability: Can be manually calibrated post-installation, allowing for on-the-fly corrections and recalibrations.

- • Versatility: Widely used across industries, from consumer electronics and telecommunications to automotive and industrial automation.

- Limitations to Consider

- • Limited Capacitance Range: While adjustable, trimmer capacitors cover a narrow range compared to standard fixed capacitors.

- • Manual Adjustment Required: Unlike digitally controlled components, they must be physically tuned, which can be a drawback in automated or remote-controlled systems.

- Trimmer capacitors play a crucial role in precision electronics, offering the flexibility to fine-tune circuits for optimal performance. Whether used in RF applications, oscillators, or high-precision sensors, their ability to adjust capacitance ensures reliability and efficiency in modern electronic designs. Despite their need for manual tuning, their accuracy, stability, and versatility make them an indispensable component in various high-frequency and calibration-sensitive applications.

General Capacitor Considerations

- • Energy Storage: Capacitors store energy in an electrostatic field, with capacitance (CCC) defined as the ratio of stored charge (QQQ) to the applied voltage (VVV):

- C=QVC = \frac{Q}{V}C=VQ

- • Parasitic Effects: Real-world capacitors exhibit parasitic inductance and resistance, which can affect their performance, especially at high frequencies.

- • Breakdown Voltage: Every capacitor has a maximum voltage it can handle before its dielectric material fails, leading to potential circuit damage.

- By understanding the strengths, limitations, and applications of each capacitor type, engineers can make informed decisions to optimize circuit performance and ensure reliability across various electronic systems.

Applications of Capacitors

Capacitors are integral to a vast range of electronic applications, from basic circuits to advanced industrial and automotive systems. Their ability to store and release electrical energy, filter signals, and stabilize voltage makes them indispensable in modern technology.

Power Management and Regulation

Power Supplies

Capacitors play a crucial role in power supply circuits, filtering noise and stabilizing voltage levels. They store excess energy and discharge it when needed, ensuring a consistent DC output for electronic devices. In switch-mode power supplies (SMPS) and linear regulators, capacitors help smooth out ripples, improving efficiency and performance.

Energy Storage in Backup Systems

Large-capacity supercapacitors (ultracapacitors) are used in uninterruptible power supplies (UPS), emergency lighting, and hybrid energy storage systems. They can deliver rapid bursts of energy, which is critical in preventing power interruptions.

Signal Processing and Audio Applications

Audio Equipment

Capacitors enhance sound quality by filtering noise and separating audio frequencies in crossover networks for speakers. They also help in tone control circuits, allowing users to adjust the bass, midrange, and treble of an audio signal.

Radio Frequency (RF) Circuits

Used in RF communication systems, capacitors filter and tune frequencies for radio transmitters, antennas, and signal processing circuits, ensuring stable communication and reducing interference.

Timing and Oscillation

Timing Circuits

Capacitors, in combination with resistors, are fundamental in timing applications such as oscillators, pulse generators, and frequency synthesizers. They control charge and discharge rates to produce precise and stable signals for microcontrollers, digital clocks, and signal generators.

Oscillators and Waveform Generators

Capacitors are vital in LC and RC oscillators, generating waveforms used in signal processing, frequency modulation (FM), and function generators. Their ability to store and release energy at specific intervals ensures stable frequency output.

Motor and Lighting Applications

Motor Starters and Power Factor Correction

In single-phase induction motors, capacitors provide the starting torque required to initiate motion. They also help improve the power factor in AC circuits, reducing reactive power losses and enhancing the efficiency of electric motors and industrial power distribution systems.

Lighting Systems

Capacitors improve the performance of fluorescent lamps, LED drivers, and HID lighting by reducing flickering and enhancing efficiency. They also compensate for reactive power, reducing overall power consumption.

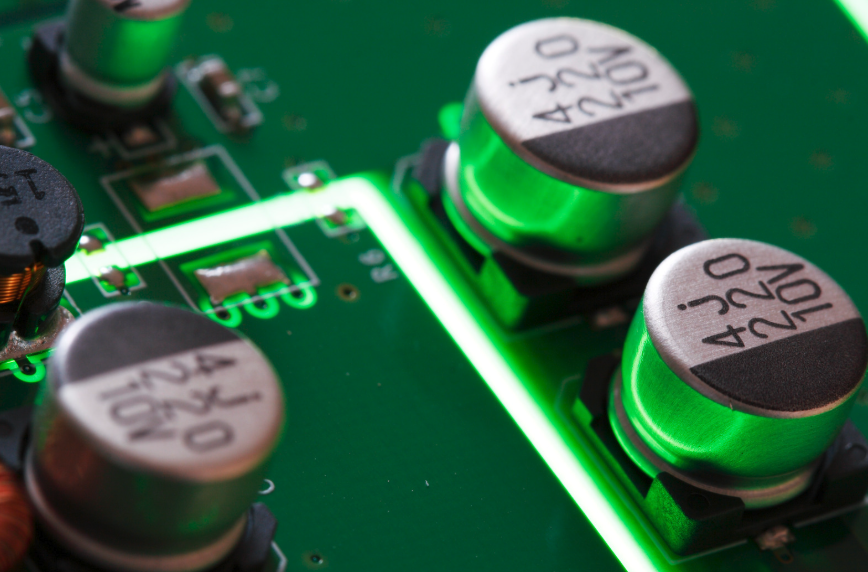

Computers and High-Speed Electronics

Power Stabilization in Computer Systems

Capacitors are widely used in computer motherboards, graphics cards, and RAM modules to filter power fluctuations and maintain stability in high-speed digital circuits. Polymer capacitors, known for their low ESR, ensure smooth power delivery, especially in high-performance computing (HPC) and gaming applications.

Data Storage and Memory Backup

Certain capacitors are used in non-volatile memory (NVM) backup solutions for flash memory and SRAM to retain critical data during power loss.

Automotive, Aerospace, and Defense Applications

Automotive Systems

Capacitors play a crucial role in engine ignition systems, electronic control units (ECUs), battery management systems (BMS), and electric vehicle (EV) power electronics. They filter high-frequency noise, stabilize voltages, and provide energy bursts for ignition and regenerative braking.

Aerospace and Military Electronics

Capacitors in radar, satellite communications, and avionics systems must withstand extreme conditions such as high radiation, temperature fluctuations, and vibration. Tantalum and ceramic capacitors are preferred for their high reliability and temperature stability.

Renewable Energy and Power Conditioning

Solar and Wind Energy Systems

Capacitors store and regulate energy in solar inverters and wind turbine generators, ensuring smooth power conversion and voltage stabilization. Film capacitors are widely used in these applications due to their long lifespan and high efficiency.

Grid Stabilization

In electrical grids, capacitors help correct power factors, reduce transmission losses, and stabilize frequency variations, ensuring efficient distribution of power across large networks.

Advanced Circuit Applications – Coupling and Decoupling

Coupling Capacitors

Used to transmit AC signals between circuit stages while blocking DC bias, ensuring clean signal transmission in amplifiers and signal processing circuits.

· Signal Transmission: Coupling capacitors are used to transmit AC signals between different stages of an electronic circuit while blocking DC components. This ability prevents DC biasing from affecting subsequent stages.

· Impedance Matching: They help in achieving impedance matching between circuit stages, ensuring maximum power transfer and minimizing signal reflection.

· Noise Reduction: By blocking DC and allowing only AC signals to pass, coupling capacitors aid in reducing unwanted noise within the circuit, enhancing the overall signal quality.

Decoupling Capacitors

Help filter high-frequency noise and provide local energy storage, stabilizing voltage supplies for sensitive integrated circuits (ICs).

· Noise Filtering: Decoupling capacitors are deployed to filter out high-frequency noise from power supply lines, ensuring a stable DC supply to critical components.

· Voltage Stabilization: These capacitors act as local energy reservoirs, providing instantaneous current to ICs (integrated circuits) and other active components during transient conditions, thereby stabilizing the voltage levels.

· Minimizing Crosstalk: In digital circuits, decoupling capacitors help minimize crosstalk by isolating different parts of the circuit and preventing unwanted interactions between high-speed signal lines.

Choosing the Right Capacitor

When selecting capacitors for coupling and decoupling, consider the following:

· Capacitance Value: Choose appropriate capacitance values based on the frequency of the signals and noise levels.

· Voltage Rating: Ensure the capacitor can handle the maximum voltage in the circuit.

· ESR (Equivalent Series Resistance): Low ESR capacitors are preferred for decoupling to efficiently filter high-frequency noise.

By understanding and properly incorporating capacitors for coupling and decoupling, you can significantly enhance the performance and reliability of your electronic designs.

Parallel Capacitor Configurations

• Enhanced Capacitance: Connecting capacitors in parallel increases the overall capacitance, improving charge storage.

• Voltage Stability: Ensures uniform voltage distribution in power supply and filtering applications.

• Load Balancing: Distributes electrical loads efficiently, reducing stress on individual components.

Practical Applications

Capacitors in parallel are commonly found in various applications, such as:

· Power Supply Smoothing: In power supplies, parallel capacitors are used to smooth out voltage fluctuations, ensuring a stable output.

· Signal Filtering: Combining capacitors in parallel can help filter out unwanted noise from signals, improving the performance of communication and audio devices.

· Energy Storage: In renewable energy systems, parallel capacitors can store and release energy more efficiently, contributing to better energy management.

Using capacitors in parallel configurations can significantly enhance a circuit’s capacitance, maintain consistent voltage, balance electrical loads, and improve various practical applications. Understanding these advantages allows engineers and technicians to design more efficient and reliable electronic systems.

How Capacitors Store Energy

Capacitors store energy in an electrostatic field between two conductive plates separated by a dielectric material. When voltage is applied:

• Charge Accumulation: One plate stores positive charge while the other accumulates negative charge.

• Electrostatic Field Formation: The energy is stored in the form of an electric field across the dielectric.

• Discharge Cycle: When needed, the stored energy is released back into the circuit, enabling rapid power bursts.

Capacitors are one of the most versatile and essential components in electronics. Their ability to store energy, regulate voltage, filter noise, and improve efficiency makes them indispensable across power systems, communication networks, computing, automotive, aerospace, and renewable energy applications. By understanding capacitor functionalities and selecting the right type, engineers can design highly efficient and reliable electronic systems for modern and future technologies.

Troubleshooting Capacitors

Capacitors play a crucial role in electronic circuits, but they can fail due to overvoltage, excessive temperature, aging, or manufacturing defects. A faulty capacitor can lead to circuit malfunctions, reduced performance, or even damage to other components. Understanding how to identify, test, and prevent capacitor failures is essential for maintaining circuit reliability.

Common Causes of Capacitor Failures

Overvoltage: Exceeding the capacitor’s voltage rating can cause dielectric breakdown, leading to failure.

Temperature Stress: Exposure to high temperatures accelerates degradation, especially in electrolytic capacitors.

Aging and Degradation: Over time, capacitors lose their effectiveness due to material breakdown and chemical aging.

Incorrect Installation: Improper polarization or voltage mismatches can lead to circuit malfunctions.

Parasitic Effects: Resistance and inductance in the capacitor’s leads can impact performance in high-frequency applications.

Troubleshooting Techniques

Visual Inspection

A quick, non-invasive check can reveal common capacitor failures. Look for:

· Bulging or swelling: Indicates gas buildup due to dielectric breakdown.

· Leaking electrolyte: Suggests internal failure in electrolytic capacitors.

· Burn marks or discoloration: Signs of overheating or electrical stress.

Solution: If any of these signs are present, replace the capacitor immediately.

Capacitance Measurement

A capacitor’s capacitance should remain close to its rated value. Use a capacitance meter to measure it.

- • If capacitance is significantly lower than the rated value, the capacitor has likely degraded.

- • A completely open circuit reading indicates a capacitor failure.

- Solution: Replace capacitors with significantly reduced capacitance.

ESR (Equivalent Series Resistance) Measurement

High ESR can cause inefficient capacitor performance, especially in power filtering and audio applications. Use an ESR meter to test:

- • A capacitor with significantly higher ESR than its rated value is failing.

- Solution: Replace capacitors with excessive ESR to restore performance.

Circuit Analysis

If a circuit is malfunctioning:

- • Check voltage fluctuations: Unstable voltage could indicate capacitor failure.

- • Observe power supply noise: Excessive noise suggests filtering capacitors are not functioning correctly.

- • Swap suspected capacitors with new ones and retest the circuit.

- Solution: If replacing a capacitor restores normal function, the original component was faulty.

Preventing Capacitor Failures

Managing Aging and Degradation

Electrolytic capacitors typically degrade over time, especially if exposed to high temperatures or voltage fluctuations.

- • Expected Lifespan: Electrolytic capacitors should be replaced every 10-15 years in critical systems, even if they appear functional.

- • Humidity and Environment: High moisture levels can accelerate degradation.

- Solution: Regularly replace old capacitors in aging equipment.

Selecting the Right Voltage Rating

Using a capacitor with an inadequate voltage rating can result in overvoltage stress and premature failure.

- • Choose capacitors with a voltage rating at least 20-50% higher than the expected circuit voltage.

- Solution: Always check and match capacitor voltage ratings with circuit requirements.

Monitoring Temperature Conditions

Capacitors have maximum temperature ratings—exceeding them can lead to early failure.

- • High-power circuits generate heat that can degrade capacitors over time.

- • Electrolytic capacitors dry out faster when exposed to excessive heat.

- Solution: Ensure adequate cooling and use high-temperature-rated capacitors when necessary.

Correct Polarization

Incorrect polarity in electrolytic capacitors can cause catastrophic failure, including explosions or leakage.

- • Check capacitor polarity before installation—the longer lead is typically the positive terminal.

- • For polarized capacitors, double-check markings on PCBs before soldering.

- Solution: Always confirm the correct orientation of capacitors in circuits.

Controlling Leakage Current

Leakage current is the small current that flows through a capacitor’s dielectric, even when it’s not supposed to.

- • Excessive leakage current leads to self-heating, reducing capacitor lifespan.

- • High leakage in low-power circuits can drain charge, affecting performance

- Solution: Regularly test leakage current to prevent premature failure.

Understanding Capacitor Limitations

While capacitors are designed for efficiency, real-world factors affect their performance.

Parasitic Inductance and Resistance

• Issue: The leads and materials introduce unwanted resistance and inductance, especially at high frequencies.

• Impact: This can distort signals in RF and high-speed circuits.

Solution: Use low-ESR capacitors and ensure proper PCB layout to minimize interference.

Breakdown Voltage

• Issue: Each capacitor has a maximum dielectric strength—exceeding this voltage causes failure.

• Impact: Breakdown leads to short circuits or permanent damage.

Solution: Always use capacitors rated above expected voltages to prevent failure.

Leakage Current Effects

- • Issue: High leakage current reduces charge retention and can lead to overheating.

- • Impact: This can shorten capacitor lifespan and reduce circuit efficiency.

- Solution: Regularly check leakage current values to prevent failures in low-power and precision circuits.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What happens when a capacitor fails?

A failed capacitor can cause:

- • Power supply instability

- • Excessive noise in circuits

- • Malfunctioning oscillators and filters

- • Overheating and potential damage to nearby components

- How can I tell if a capacitor is faulty without special equipment?

Look for visible damage, such as bulging, leaking, or discoloration. If unsure, replace the capacitor and test the circuit for improvements.

- What causes capacitors to leak electrolyte?

- • Overheating from excessive current or poor ventilation

- • Manufacturing defects in the dielectric material

- • Overvoltage stress beyond rated limits

- What is the difference between ESR and capacitance failure?

- • Low capacitance failure means the capacitor no longer stores charge effectively.

- • High ESR failure means the capacitor introduces excessive resistance, reducing efficiency.

- How often should capacitors be replaced?

- • Electrolytic capacitors: Every 10-15 years in critical applications.

- • Film and ceramic capacitors: Can last decades unless physically damaged.

- Troubleshooting capacitors is essential for maintaining circuit efficiency, stability, and longevity. Regular visual inspections, capacitance measurements, and ESR testing can identify failing capacitors before they cause damage. By selecting the right capacitor types, ensuring proper installation, and monitoring real-world limitations, engineers can prevent common capacitor failures and improve the reliability of electronic systems.

Small Component, Big Impact

Capacitors are essential electronic components used in a wide range of applications. From power supplies and audio systems to cutting-edge industrial and automotive applications, these components are fundamental to circuit performance and reliability. Understanding their functionality, types, and real-world applications empowers you to design, troubleshoot, and optimize electronic circuits with confidence.

As technology advances, capacitors will continue to drive innovation, enabling more efficient power management, enhanced signal processing, and next-generation electronic devices. Whether you're selecting the right capacitor for a project or troubleshooting circuit issues, a solid understanding of these components is essential.

Safety Tip: Always handle capacitors with caution—even when disconnected, they can retain a charge that may pose a hazard. Follow best practices to ensure safe and effective use.

Need a Part? We’ve Got You Covered!

Looking for capacitors or other electronic components? Our experts are here to help! Contact us today for personalized assistance in finding the right part for your needs.